Civic Hymns and Civil Disobedience: Creating a Civil Religion Playlist to Reclaim the Civil Religion for All

Recent events in the United States reveal how divided this nation has become. In part, this is due to a loss of the ability to communicate with people who are not like them socially or politically. The US has a distinct civil religion that, until recently, was sacrosanct; part of this civil religion is civic hymns that serve to both support and question the establishment. Indeed, music can be one arena in which the civil religion can be reclaimed by all citizens, particularly when considered as an aspect of youth culture. The authors propose a civil religion playlist—a set of songs for teachers on all levels to use as tools to engage their students in political discourse in the hopes of producing active citizens who can engage with one another. While not purporting to be exhaustive or definitive, the playlist is a means of beginning a conversation and one tool for educators to actively engage their students. By doing such, the authors also suggest a reperiodization of the latter half of 20th Century US history to present a curriculum of youth culture.

Our Argument

There exists a civil religion in the United States, a set of ideas, norms, and practices that purport to be secular, but are rooted in strong Judeo-Christian traditions. Accordingly, there are certain elements of Americana that assume a religious reverence among many citizens: symbols, songs, places that take on a nearly holy status in the minds of many citizens. Our civil religion’s holiest of traditions revolve around the presidential election. At just after noon on January 20, 2021, President Joe Biden stood on the steps of the Capitol and began his inaugural address by saying, “the American story depends not on any one of us, not on some of us, but on all of us, on we the people, who seek a more perfect union.” Throughout the speech, the new president of the United States of American emphasized the unity that is embedded in the nation’s very name. On the same location a mere two weeks earlier, violence that had taken place on that spot. Within the Capitol building blood was spilled, neo-Nazi and Confederate flags were raised, and the walls were smeared with feces.

The reporting that emerged directly reflected how deeply runs the civil religion in the country: the Capitol building was referred to as the “temple of liberty”; the Senate and House floors were referred to as sanctums, their spaces sacrosanct. The actions of the domestic terrorists who attempted insurrection that day were referred to as defiling these places, violating who we are as a people. U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer (D-NY) described the attack on the Senate building as “This temple to democracy was desecrated” (Schumer, “Statement”). Sen. Amy Klobuchar in her introduction to the inaugural address referred to the Capitol as the “cathedral of democracy,” and the cathedral had been desecrated. Certainly, most political speeches trade heavily in the imagery of the civil religion, but those events of the early days of 2021 provided vivid examples of how the civil religion functions (or at least ought to function) as providing an ideological grounding for American life. If it wasn’t clear before those events, it is certainly clear in their wake: the civil religion no longer effectively functions as a unifying social force.

In the days following the November election, as it became clear that Biden had got enough votes to clear the 270 electoral vote threshold, a strange phenomenon began to occur. Supporters of the president-elect began to unfurl their American flags. A late-November 2020 report from Politico, “Time for My Flag to Go Up“, noted that for many year people on the left side of the political aisle had shied away from overt displays of the Star and Stripes, because “for many people on both sides of the political chasm, the flag had been recast as a kind of shorthand, an extension of the MAGA hat—sending an instant message of which side you were on, or inspiring stereotypes that pulled the country even further apart” (Weiss). In a certain sense, this particular trapping of the civil religion had been successfully appropriated by members of the political right. The civil religion, rather than serving the underlying function of bringing us together had, in effect, just become another partisan wedge between countrymen.

A Brief History

Of course, this political divide over the images of the civil religion did not arise overnight, or even over the course of a single Trump presidential term. Certainly, the angry Twitter diatribes against National Football League players kneeling in protest of racial injustice during the national anthem had accelerated the members of the right “rallying around the flag,” and it also made it difficult for members of the left to use the flag as a symbol of their own national identity. Still, this political divide over the use of the trappings of civil religion had far deeper roots than the more recent Black Lives Matter protests. During the Reagan administration, the push for an anti-flag burning Constitutional amendment was born of this same desire to cast the ownership of the civil religion as a partisan issue, and much of these sentiments were emotional hold-overs from the Civil Rights, women’s rights, and anti-Vietnam protests of the 1960s and 1970s.

Since the mid-twentieth century, popular culture evidenced a growing ambivalence to the civil religion among people (particularly young people) on the left. This was certainly the case with much protest music of the 1960s and beyond. Creedence Clearwater Revival, in their song, “Fortunate Son,” provides perhaps the most vivid example of that: “Some folks are born, made to wave the flag, Ooh, they’re red, white, and blue/ And when the band plays Hail to the Chief/ Ooh, they point the cannon at you.” There was a growing sense in the 1960s and beyond that the civil religion itself had become associated with overt militarism and a specific set of socio-cultural beliefs increasingly divergent from the leftist zeitgeist. CCR was, of course, not the only such example. In their 1970 Madison Square Garden concert, Jim Morrison of The Doors asked the audience to “show some respect” and stand for “the Anthem,” only to have the band belt out their cover of the Motown hit “Money (That’s What I Want).” Since at least as early as the 1960s the ways that members of the political left and right expressed their own sense of patriotism had begun to bifurcate.

This cultural split has made the civil religion a more complex and less unifying aspect of American culture. One could argue that some of the 1960’s popular protest songs have become aspects of American civil religion. For their part, Creedence Clearwater Revival made an unsuccessful bid to stop Donald Trump from playing “Fortunate Son” to warm up his rally crowds. Likewise, the Rolling Stones found themselves in precisely the same situation, trying to get Trump to discontinue his use of their “You Can’t Always Get What You Want”. Despite expressing a political viewpoint that is startlingly at odds with Trump’s own, these songs have become a shared cultural experience and have become placeholders for a sort of anti-establishment patriotism. On the other hand, even singers with a long history of protest music have recently begun to try their hands at patriotic anthems. Newly naturalized American citizen Neil Young, for instance, released his “Lookin’ for a Leader” late summer of 2020, even if it is still tinged with social critique (“America is beautiful/ But she has an ugly side… We’re lookin’ for a leader/ With the great spirit on his side”).

Two Types of Civic Hymns

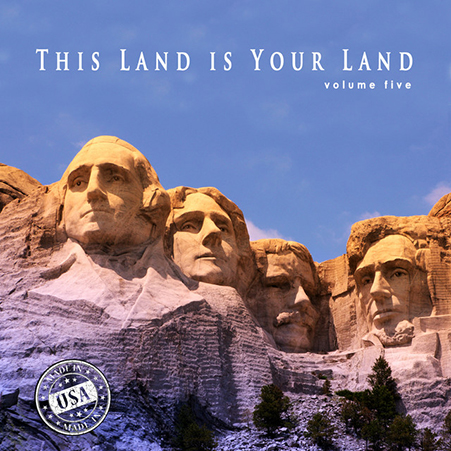

The tendency to see protest anthems and patriotic anthems on opposite ends of a partisan continuum misrepresents some of the complexities of the functions of the two types of songs. While protest anthems serve as a social critique, they are also intended to call attention to a specific issue and unify people behind a common cause. Moreover, when enough people rally around those protest songs, they become civic hymns of their own. Consider, for example, Dion’s “Abraham, Martin, and John,” a song which in the context of the 1960s might have been a protest song intended to highlight the assassinations of leaders important to the expansion of civil rights to African Americans, but the message is far more unifying now than it would have been when it was recorded. In the same way, Woody Guthrie’s “This Land Is Your Land,” once a song meant to satirize “God Bless America” and originally titled “God Blessed America for Me,” has become a patriotic anthem in its own right. Insofar as protest songs are meant to bring together people and direct their energies toward a common cause, they are similar in function to and can even become patriotic anthems.

Patriotic anthems, despite their seeming function of presenting patriotic sentiment around which disparate groups can rally in the interest of developing a common national identity, can themselves be divisive. In the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks, Toby Keith recorded his patriotic anthem “Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue”. While it was ostensibly intended to create patriotic fervor in his audience, lyrics like “And you’ll be sorry you messed with the U.S. of A./ ‘Cause we’ll put a boot in your ass/ It’s the American way” mark those patriotic sentiments as belonging only to the segment of the citizenry of the United States who supported war in Southwest Asia, thereby attempting to claim patriotism as the sole province of people adopting a particular partisan identity. As such, the song serves to divide as much (or more) than unify and ultimately undermines a sense of common national identity.

Democracy in action has always had the potential to be messy in its execution, but most used to agree that it was worth engaging in. There is no one solution to fix all that ails democracy in the US; however, educators on all levels must say enough is enough and begin stepping up to do what they can. In part, educators can reclaim the civil religion as a tool for engaging in democracy, teaching their students to not cultishly follow what they are told and not to demonize those with whom they disagree. Just as music has been integral to voices of dissent and support, the authors argue that music can be integral to showing students that multiple points of view are welcome in our society; that patriotic hymns can be both patriotic and protest-oriented.

To this end, the authors propose a civil religion playlist—a set of songs for teachers on all levels to use as tools to engage their students in the study of US history and perform political discourse in the hopes of producing active citizens and reclaiming the civil religion for all. This website provides an analysis of protest songs and patriotic anthems from a variety of eras across the second half of the twentieth century, arguing for a reconceptualization of the dichotomy that has arisen and separates the two types of songs. In so doing, it seeks simultaneously to uplift the importance of the civic hymn as a means of creating an inclusive conception of what it means to be an American, a grounding condition necessary for the continued functioning of a democratic society, and the importance of the protest anthem in highlighting social injustice and pulling people together to combat that injustice, a necessary precondition to forming a more perfect union. These two types of songs do not lie at opposite ends of a continuum but serve compatible roles in the maintenance of civil society.

[1] The authors wish to thank the audience participants from their sessions at the 2017 History of Education Society Annual Meeting and the 2018 Popular Culture Association National Conference who made several outstanding suggestions to improve the playlist.